The Ivory Child

The Ivory Child She and Allan

She and Allan The People of the Mist

The People of the Mist She

She Morning Star

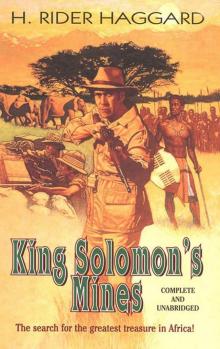

Morning Star King Solomon's Mines

King Solomon's Mines She: A History of Adventure

She: A History of Adventure Cleopatra

Cleopatra Ayesha, the Return of She

Ayesha, the Return of She Eric Brighteyes

Eric Brighteyes Red Eve

Red Eve Fair Margaret

Fair Margaret When the World Shook

When the World Shook Lysbeth, a Tale of the Dutch

Lysbeth, a Tale of the Dutch Moon of Israel: A Tale of the Exodus

Moon of Israel: A Tale of the Exodus Long Odds

Long Odds The Ghost Kings

The Ghost Kings Pearl-Maiden: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

Pearl-Maiden: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem Allan and the Holy Flower

Allan and the Holy Flower Smith and the Pharaohs, and other Tales

Smith and the Pharaohs, and other Tales The Wanderer's Necklace

The Wanderer's Necklace Dawn

Dawn The Lady of Blossholme

The Lady of Blossholme Stella Fregelius: A Tale of Three Destinies

Stella Fregelius: A Tale of Three Destinies Allan Quatermain

Allan Quatermain Montezuma's Daughter

Montezuma's Daughter Jess

Jess The Brethren

The Brethren Allan's Wife

Allan's Wife Child of Storm

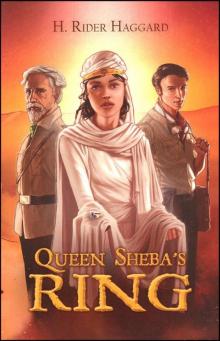

Child of Storm Queen Sheba's Ring

Queen Sheba's Ring King Solomon's Mines (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

King Solomon's Mines (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Complete Allan Quatermain Omnibus - Volumes 1 - 10

Complete Allan Quatermain Omnibus - Volumes 1 - 10